I recently went to Coventry to write a feature for Anglotopia magazine. Before I went, everyone told me there were no old buildings in Coventry. The whole city was destroyed by bombs in the Second World War, they said. Well, that simply wasn’t true. Yes, the WWII bombs did bring devastation to the city. And yes, the famous cathedral is still in ruins as a reminder. But, I found I could hardly turn a corner without finding a heritage building.

Medieval Architecture

It’s worth noting that, in medieval times, Coventry was one of the largest cities in England and there is still plenty of medieval architecture today. There are gatehouses from the city walls and medieval ruins that everyone just walks past because there is just so much to see here.

Next to Holy Trinity Church, Lychgate Cottages is a lovely timber-framed building and the only surviving part of St Mary’s Priory. While these were used as church offices there are plans to turn them into holiday accommodation.

The three spires, which have dominated the city skyline since the 14th century, are from the ruined cathedral, Christ Church (Greyfriars) – only the spire remains – and Holy Trinity Church – the only one still in use.

Holy Trinity Church

Holy Trinity Church is almost next door to the cathedral. It dates back to the 12th century (although most was rebuilt during the 1300s). Considering the nearby bombing it is incredible that it survived the Blitz. This was the only building left standing on Broadgate (and the only large historic building in Coventry left intact after WWII). The only damage to Holy Trinity Church was the loss of two stained glass windows at the East and West ends. (The replacement East window that was lost during the Blitz is called the Bride’s window because it was paid for by the couples who married in the church during the 1940s and 1950s.)

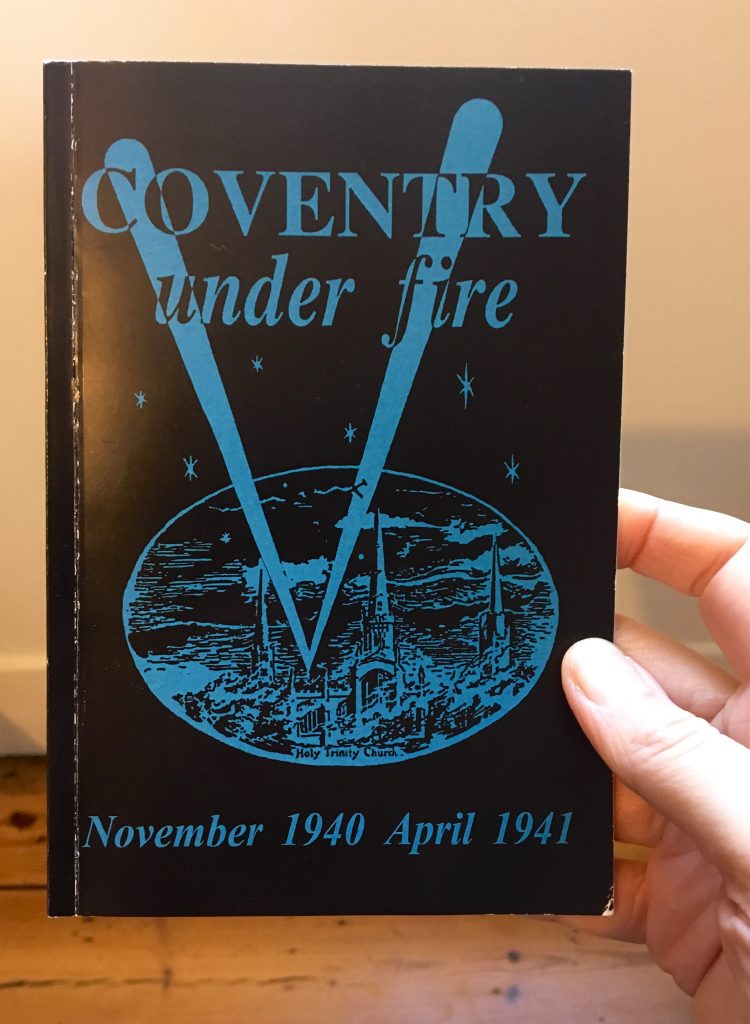

While there, I picked up this fascinating book by Reverend Clitheroe who was the Vicar of Holy Trinity Coventry during WWII. He explains how he kept watch at the church every night during the raids so he could put out fires quickly. It includes photos of the area before and after the bombing, plus tales of immense bravery and resolve. They just got on with things whatever happened. What else could they do?

Doom Painting

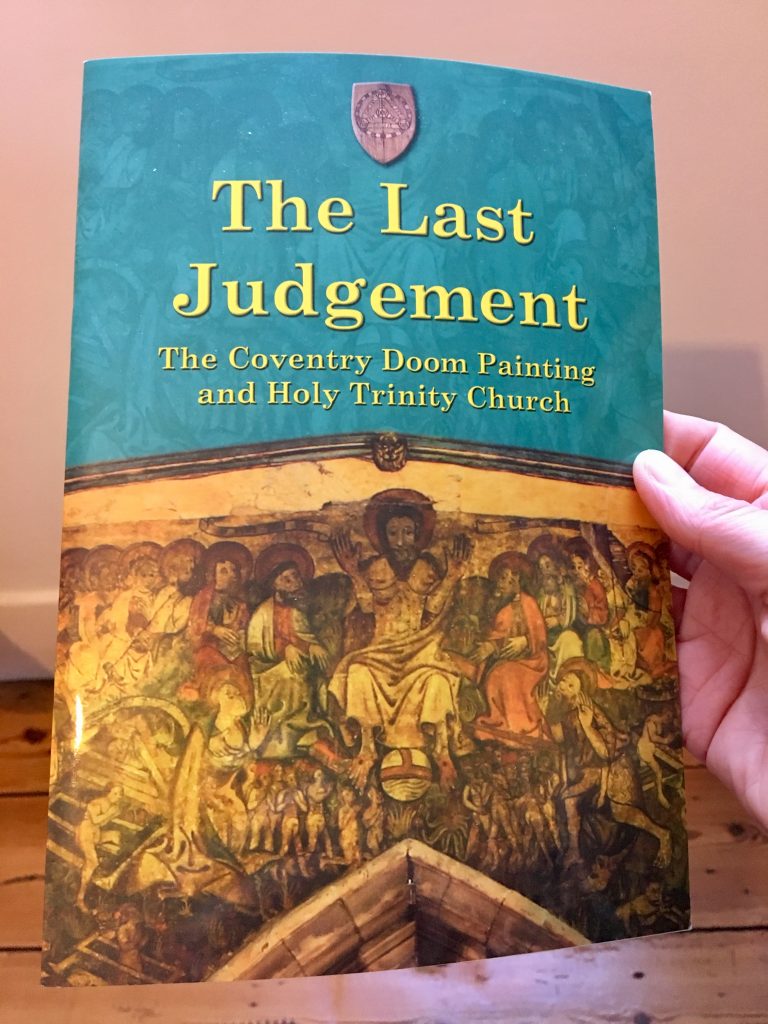

Most visitors to Holy Trinity come to see the Coventry Doom painting of the Last Judgement – an impressive medieval painting created in the 1430s on the chancel wall. (There had been an earthquake in Coventry in 1426 and the townspeople believed it was God’s wrath for their sins.) The painting was rediscovered in the 1830s but the varnish to preserve it turned black so it was soon hidden again. After nearly 20 years of conservation and restoration, it was unveiled in 2004.

The painting is very high up so you may prefer to buy the guidebook to study in detail as it is remarkable. Christ is in the centre with the dead rising from graves on the left. Look closely and you should spot the three Coventry ale wives on the right, chained and being led to the mouth of Hell. These women represented the damnation of those who sold watered down beer. (It wasn’t the weakened beer so much that was the problem as the fact the water was so contaminated which was why people drank beer instead.)

More to See

You won’t need all day but set aside up to an hour to look around Holy Trinity. The volunteers inside are always happy to answer questions and I discovered lots of interesting stories from them.

There’s a bishop’s chair here because during the 19th century Rev Dr Walter Farquhar Hook wanted to welcome his friend, the Bishop of Ross, Moray and Argyll, to the church. At the time, anyone who had taken holy orders from the Church of Scotland was forbidden from stepping inside an English church. To get around this problem, Hook had a chair made to carry his friend into the church. It was a high seat so the Bishop’s legs could dangle but his feet remained off the ground.

And as this is a crown church, do look in the Marler’s Chapel to see a section of the 1953 gold coronation carpet.

Emily Stearns

Following a chat with the team at Holy Trinity, I learned about a Coventry woman with a US connection. They would like to track down any family or friends in the US to find out more about her.

Born in Coventry in 1857, Emily Stearns was the daughter of Mr and Mrs William Henry. After her father’s death and her mother’s second marriage to Edward Simms (who was organist at St Michael’s Church for many years) she went to New York. In September 1891, she married Mr H.K. Stearns – a silk manufacturer based in Brooklyn.

In 1892, they moved from New York to set up Stearns Silk Mill at Memorial Ave and Oliver St in Williamsport, PA. Many mills moved from New York to Williamsport at the time seeking female workers who, eager for jobs, would work for lower wages than city girls. The mill was set up by John N. Stearns (father of H.K. Stearns?) and by 1902, it was the largest silk mill in the region and employed over 1,000 people. It closed in 1933.

The YWCA Northcentral PA, established in 1893, created a space for the local factory girls to go during their lunch break where they could eat and relax. In 1894, John N. Stearns’ Silk Milk donated $150 to the YWCA to create a specific lunch room for girls who worked at the mill.

According to an inclusion in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper dated 16 March 1892, H.K. Stearns, president of the Seventh Ward Republican Association, died of pneumonia. So it would appear that Emily was widowed just a year after getting married.

We’re not sure when she left the US but Emily did return to Coventry where she settled back to living with her mother.

She was prominent in the city and was keenly interested in the social and welfare work of the city. She helped found the Coventry YWCA and became its first President. She continued in the role for 30 years and spent the greater part of her life associated with organisations for the welfare of women. She was instrumental in welcoming and supporting the many women who travelled to Coventry to work in the factories after the First World War.

Emily Stearns was a member of Holy Trinity Church and became its first female Warden. In 1920 she was appointed one of the first Justices of the Peace even though she was still an American citizen (it was not until 1924 that she was re-nationalised).

Emily died, aged 73 years, in February 1930 at home at 14 Park Road, Coventry. Her sister was Mrs R.B. Caldicott of Croft Gate, Queen’s Road, Coventry, who had been married to Colonel Richard Caldicott.

No Organ

One thing I quickly noticed is that Holy Trinity doesn’t have an organ anymore. Well, it does have an electric organ but not a church pipe organ like you would expect to find. The old organ was condemned and removed in 2008 so there is a fundraising campaign to fulfil their ‘pipe dream’ of buying a Grade I historic organ.

A life-long supporter of the choir, Emily Stearns left a donation in her will for an essential part of the organ to be purchased. The team at Holy Trinity would like to trace her family and friends to see if they too would like to help donate towards the replacement organ. The Holy Trinity team can be contacted at: organappeal@holytrinitycoventry.org.uk