Can I tempt you to 90 minutes in a damp, disused underground station where you may have to wait in darkness? Go on, it’s well worth it.

Down Street London underground station opened on 15 March 1907. It was on the new Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway (GNP&BR) which we now call the Piccadilly line.

Its importance is not as a tube station though but as safe office headquarters during World War Two and as a secret refuge for a very famous leader.

Street Level

As the station wasn’t permitted on the main road (Piccadilly) it was located down a side road, with long underground tunnels to connect to the line running under Piccadilly itself.

The surface station was designed by Leslie Green who was commissioned to design 50 London Underground stations in the early 1900s. His distinctive style is easily recognisable with a classical Arts and Crafts style and ox-blood glazed tiled façade. He used a steel frame roof to support buildings on top, meaning railways could charge rent.

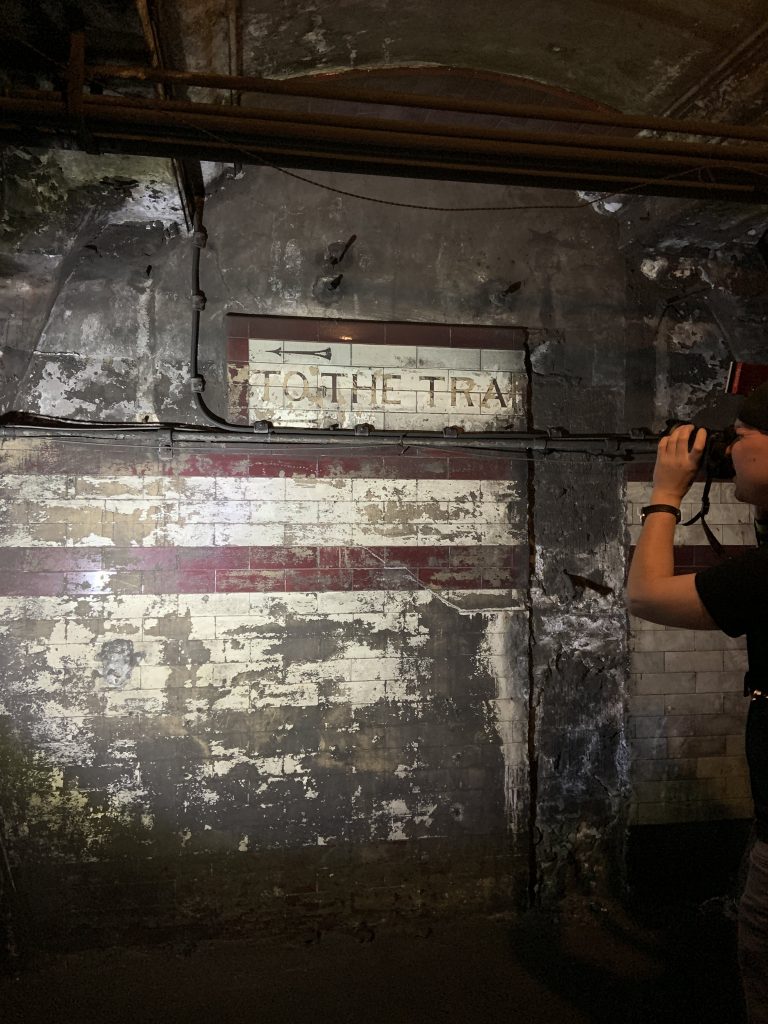

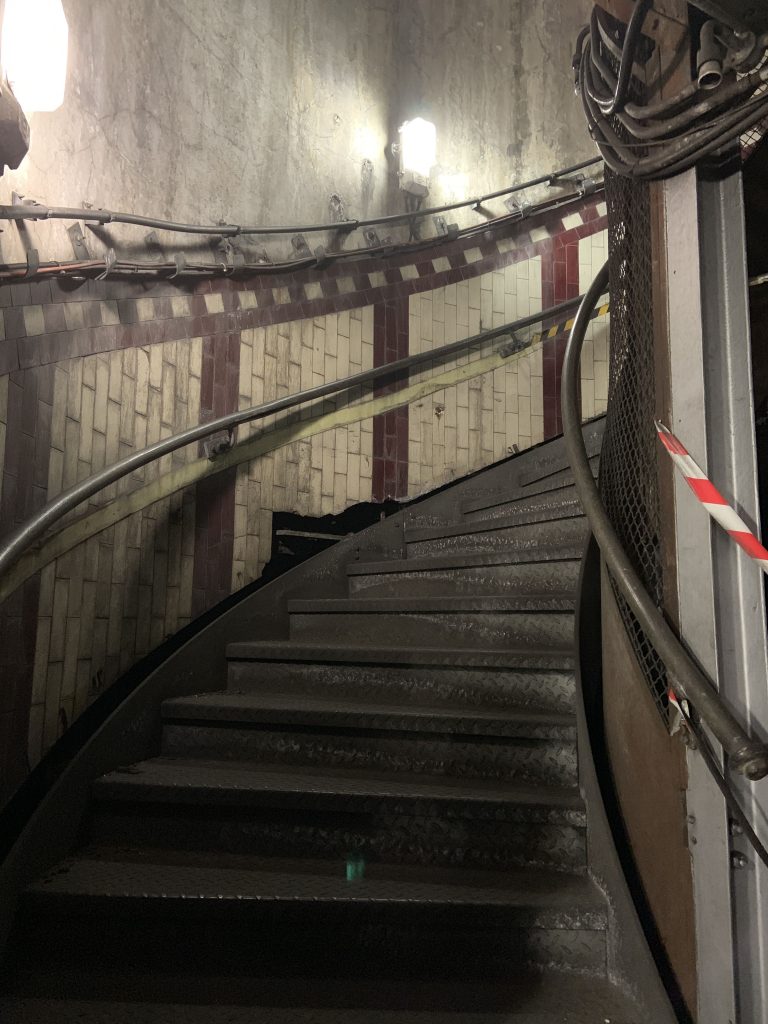

Inside the Leslie Green stations, different tile colour schemes helped illiterate passengers identify each station. Here, there are maroon and cream tiles.

Opening

The entrance was where the newsagent is today. When the station opened in 1907, there were protests as there were concerns a station in upper class Mayfair may bring the riff-raff to the area. Local residents had ensured there was no signage on Piccadilly, and they didn’t need the station either as they largely had their own transport.

Closing

By 1909 there was a reduced service, and from 1918 there was no Sunday service. Down Street only lasted for 25 years and closed on 21 May 1932. The lift shaft was removed in 1932 as it could be used in another station.

It was never a busy station with the long walk from the station entrance to the platforms, plus Hyde Park Corner and Green Park were nearby and had escalators.

Once closed, the passageways were then used as a ventilation shaft for the Piccadilly line.

REC

Preparations to defend the nation before the outbreak of war meant the Railway Executive Committee (REC) was formed in September 1938. The REC was tasked with keeping all trains running throughout World War Two across England, Scotland and Wales (including London Underground). This was not just passenger trains but also munition trains and milk trains too.

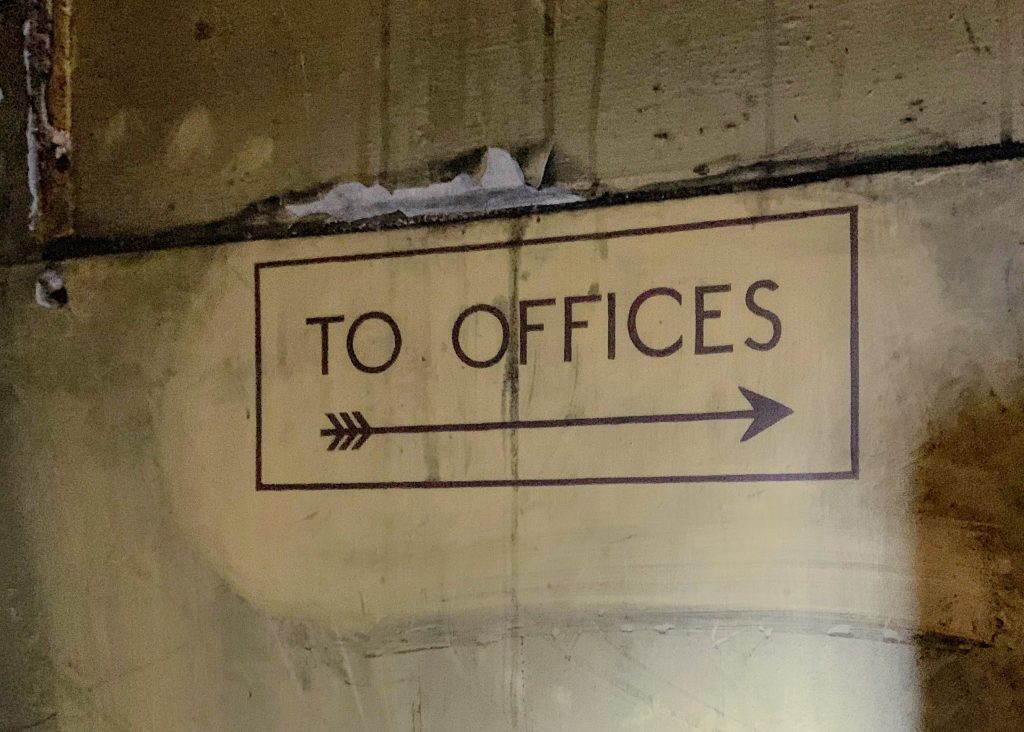

With fears that their current Westminster HQ, a sizeable building close to the Houses of Parliament, wouldn’t survive an aerial attack, it was Gerald J Cole Deacon, REC Secretary, that remembered the abandoned tunnels of Down Street. By the start of March 1939, the government confirmed the REC was an essential service and by the end of the month, the REC had signed a lease from London Transport (LT) for Down Street station to be their bomb-proof wartime headquarters. Plans were approved by April 1939 and construction began on converting the space. The enclosed platform areas and space in the passages were divided up into offices, meeting rooms, toilets and dormitories. It even had a telephone exchange. Canary yellow paint was used to make the area seem less industrial.

Moved in From 1935

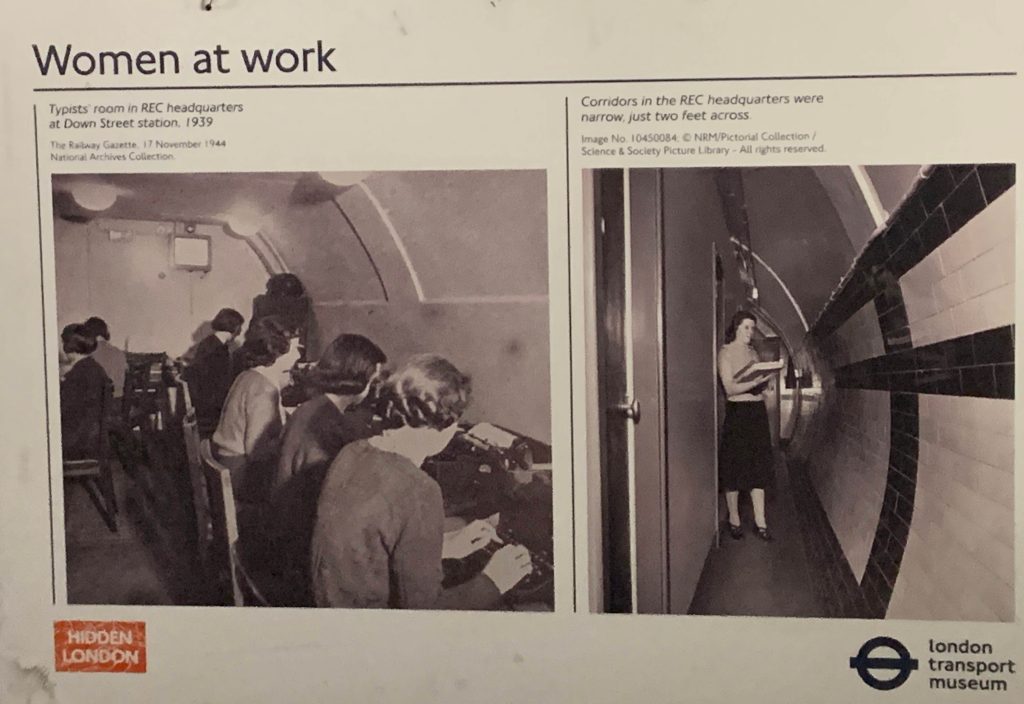

40 staff worked here, including 8 female typists, plus phone operators and schedulers. Work continued for 24 hours a day so staff stayed for 2-3 weeks working 12-hour shifts.

When the REC first moved in there were only chemical toilets but proper toilets, sinks and bathrooms were soon installed. The class system was alive and well in the 1940s so there were Executive bathrooms and staff toilets and sinks. A memo has been found for an order of 12 fluffy red towels from Harrods for the Executive bathrooms (for the 12 Executives who worked here).

There were nineteen staff dormitories, eight of which accommodated three people in shared, tiered bunk beds. Executives had private rooms and the furniture came from London railway hotels.

Executive rights also meant they could stop a train (by switching on a red light to alert a driver) and leave the ‘offices’ by train instead of climbing up stairs to ground level. There was a lift but reports mention it getting stuck some times.

There were kitchens down here with a Head Chef and two assistants, plus a couple of waiters. (There’s a vent in the kitchen ceiling but no-one has yet worked out where it leads to.)

It was considered a privilege to work here as you were ‘off rations’ so enjoyed a better diet than your family at ground level. In the Executive Dining Room you can still see a bell on the wall for calling a waiter so they didn’t stay in the room and hear private conversations.

There were no reports of rats and mice at the station (which is astonishing as mice live at most stations now) but there are reports of cockroach infestations.

Churchill

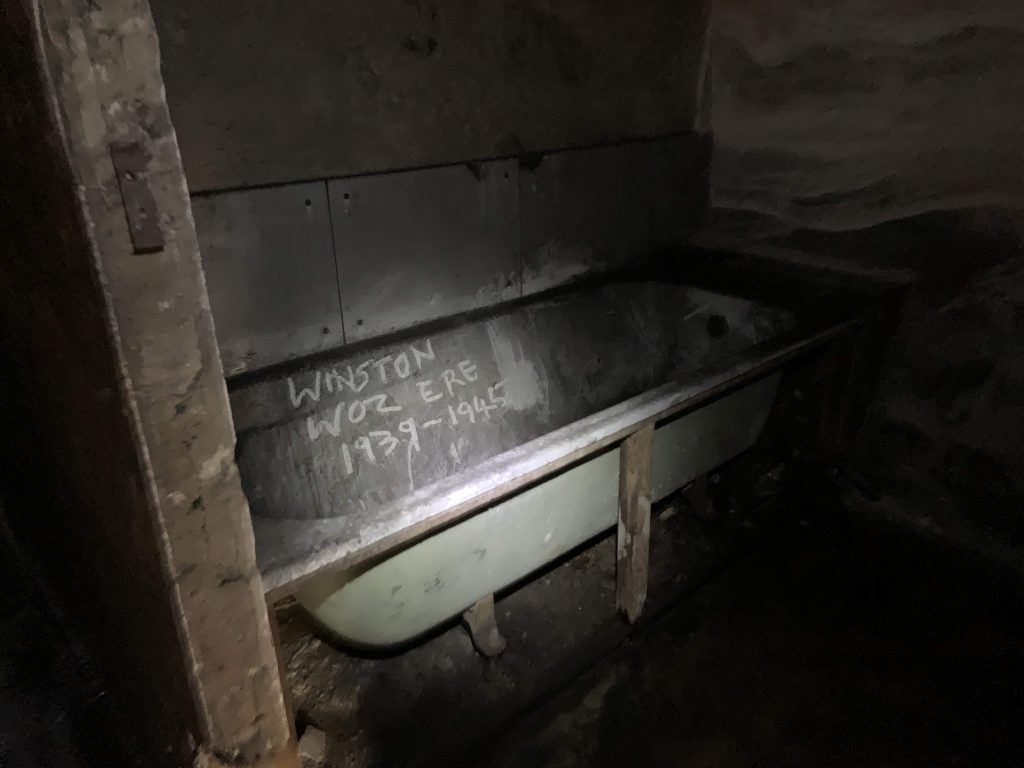

Prime Minister Winston Churchill secretly took refuge here at the height of the Blitz.

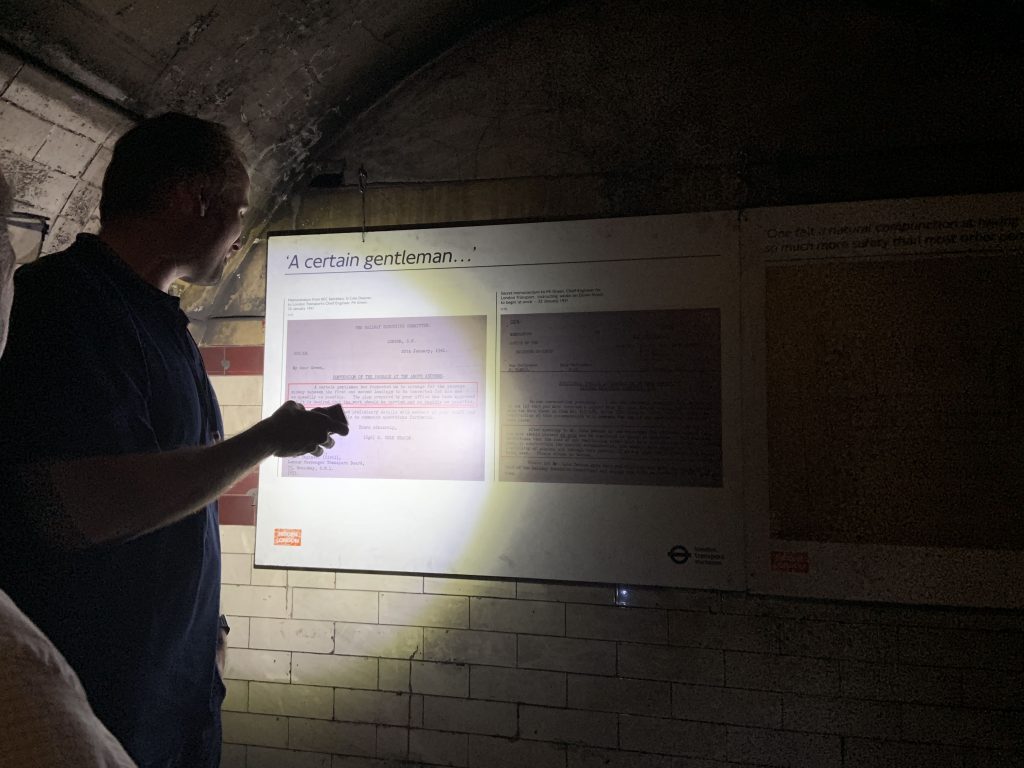

I was surprised to hear that the Cabinet War Rooms wouldn’t have survived a direct hit from a bomb above during the Blitz (it was later strengthened) but Down Street station was safe as it was so far underground and had been reinforced. Winston Churchill was friends with Josiah Wedgwood, brother of Sir Ralph Wedgewood, the REC Chairman, which is how the idea of staying at Down Street station for safety came about.

Churchill stayed in Cole Deacon’s office (REC Secretary) for 40 nights between October and December 1940 during the Blitz. He mentions Down Street in his memoirs and refers to it affectionately as “The Burrow”. Apparently, those who worked here referred to it as “The Dungeon”.

Success

The REC was able to keep working unhindered by air raids above. A high explosive bomb did fall on Down Street (not a direct hit on the station but on the same road).

The success of Down Street station as offices was demonstrated by the REC’s decision to remain at the site beyond the end of the Second World War. The REC finally left on 31 December 1947.

The station was returned to its previous purpose to help ventilate the Piccadilly line. Little is known about the station from 1947 until the London Transport Museum started their Hidden London tours a few years ago.

The Tour

The dark and dirty warning on this tour is appropriate. We were issued with TFL-approved torches and, because of the proximity to live tube lines, there were moments of total darkness. “TOUR STOP, LIGHTS OUT” was called so we turned our torches off and stood still so as not to startle the passing Piccadilly line drivers.

Everything is covered in a thick layer of dusty grime so do not touch the walls. Apparently, 70% of the dust found in these abandoned stations is made up of human skin and hair.

The tour starts in a nearby building for the health and safety briefing and then it’s 103 steps (23 narrow straight steps and then 103 on the spiral staircase) to get around 22 metres (72 feet) below Piccadilly.

The trains can be heard nearby but are really close when you get to the rooms that are actually built on the platforms. Only a thin wall separated these rooms from the Piccadilly line track. The trains passing do not slow down as they would for a passenger station so the woosh sound of a full-speed train is quite different.

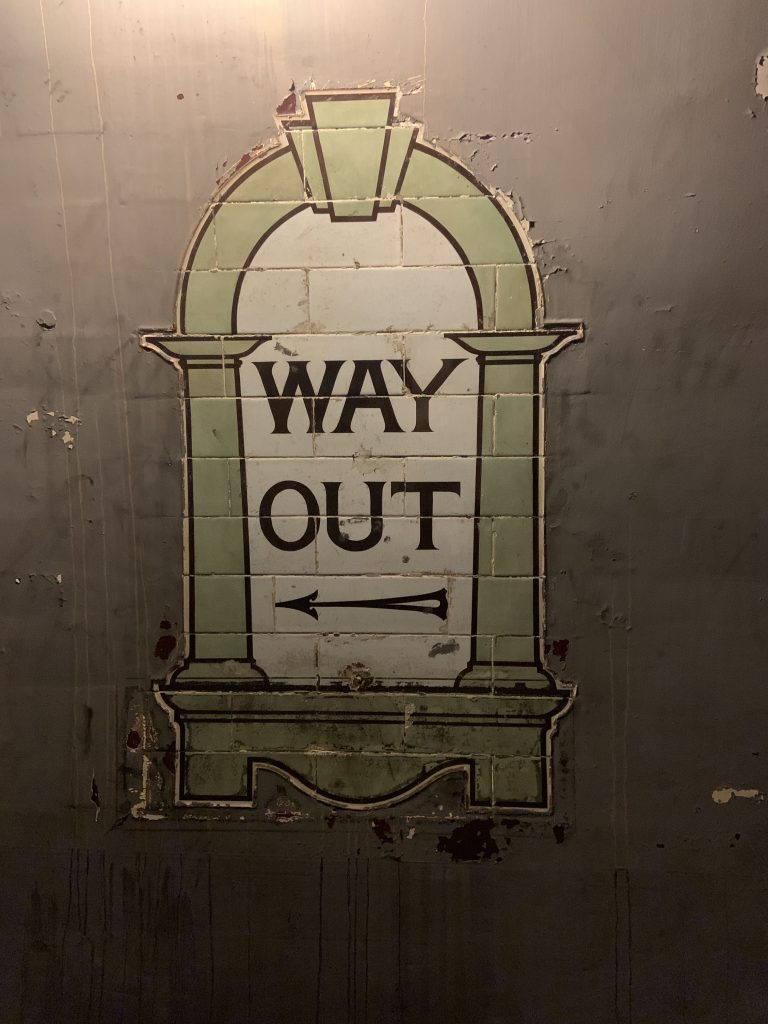

It was easy to forget you were on the tube platform so the Way Out cartouche was a good reminder.

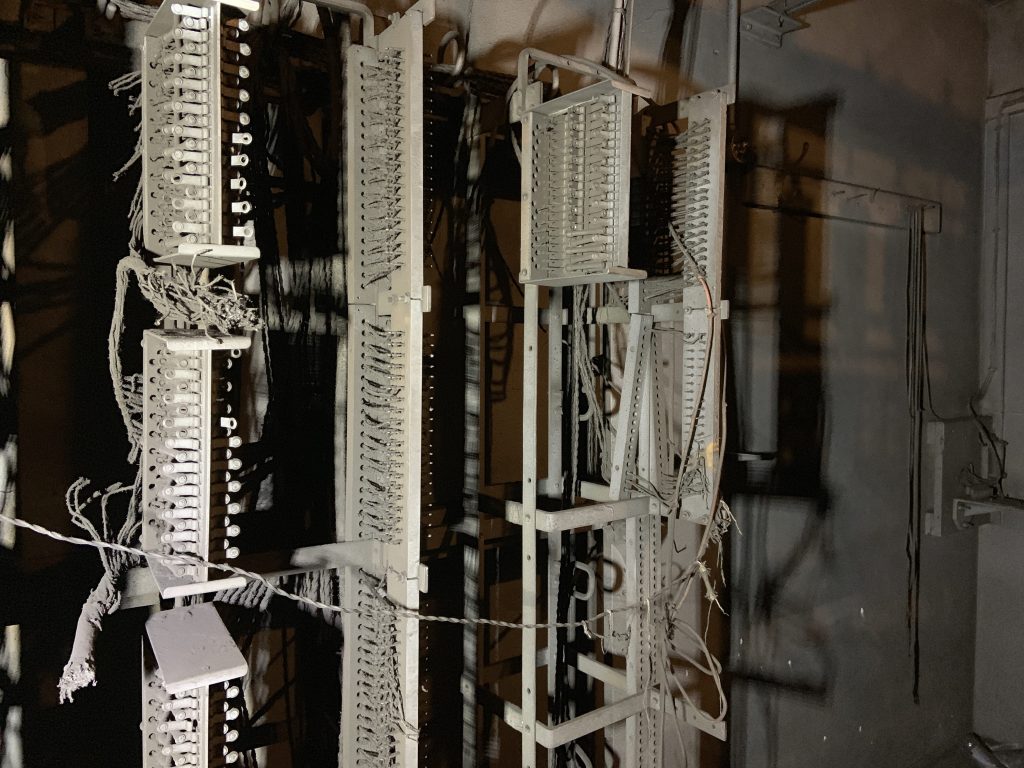

I wasn’t expecting to see a 50-line telephone exchange but it had to be in central London and here was safe – even if somewhat noisy from the close Piccadilly line trains. The telephone lines were needed for vital coordination of a railway system under fire. There was also a link between here and Selfridges for American communication.

The platform on the other side had duplicators (photocopiers) and a teleprinter. Motorbike dispatch riders waiting in the Mews at street level.

It was incredible to be so close to trains that sped past on the other side of a grill. Do look out on the right-hand side of the train when you travel between Hyde Park Corner and Green Park on the Piccadilly line as you may spot the station and see a tour group looking back at you.

Another unusual find, not at any other stations, is the tiles marked with the manufacturer’s name: Simpson & Sons.

Tour Information

Our Guides were Nigel and Ben. At the end of the tour, Ben told us it was his first tour and, while he had said he was new and still learning, he was clearly already doing a great job.

After climbing back up to ground level, we handed in our torches and everyone on the tour was presented with a ‘Top Secret’ folder produced by the London Transport Museum with fascinating information about Down Street station.

Tours do not run every day and you do need to book well in advance. Tickets are limited to a small group (12 places available on each tour).

Official Website: https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/whats-on/hidden-london/down-street

Sign up for the London Transport Museum newsletter to be first to hear about Hidden London tours.

We were told a new Hidden London tour is coming soon which is exciting news as I’ve now been on all the underground tours available.

Disclaimer: As is common in the travel industry, the writer was provided with complimentary tickets for review purposes. While it has not influenced this review, AboutLondonLaura.com believes in full disclosure of all potential conflicts of interest.