That’s probably the longest unintentional headline I’ve ever written but I think it gets the point across. When out and about in London, it’s always worth looking up, down and all around as you’ll often spot something unusual. It’s the joy of an old city that has evolved with layers left to discover unexpectedly.

For this list, I wanted to choose things that meet the title’s criteria well and not ‘hidden gems’ such as St Dunstan in the East, God’s Own Junkyard or even the Bourdon Place Statues. Nor did I want ‘secret London’ ideas such as the WW2 Bunker in North London.

There are blue plaques and other memorials all over London but they have not been included here either, although many are worth seeing such as the Ziggy Stardust blue plaque on Heddon Street.

So, here are ten things to notice and nonchalantly point out to impress your friends.

1. Metropolitan Police Hook

I worked in Covent Garden for six years and didn’t notice this in all that time. But a friend in the Metropolitan Police shared the tip and I’ve been passing it on ever since.

On the edge of the Covent Garden area, there’s a Metropolitan Police coat hook fixed to a wall. It’s on the outside of the black-tiled building opposite the Leicester Square tube exit on Great Newport Street, WC2, near the red telephone box.

The location is near a busy junction where six roads meet. In days gone by, a policeman was regularly posted here to help with the traffic flow.

Apparently, there was initially a simple nail in the wall for a policeman to hang his cape on (capes were used during wet weather). But it’s reported that this hook was added in the 1930s by a builder who was working on the property and wanted to add something more elegant for the local constabulary.

2. Ice cream Railing in Fitzrovia

I think I first heard about this from a friend at Londonist. But the hat tip goes to Peter Berthoud who shared the background to why you can find an upturned ice cream cone incorporated into the front railings of an art gallery in Fitzrovia.

This is the former offices of Shirt Sleeve Studio, a model-making and design company set up by husband and wife team Nancy Fouts and Malcolm Fowler in the late 1960s. The company’s best known collaboration was the 1987 ‘Tate Gallery by Tube‘ poster with the tube lines represented with oil paints squeezed from the paint tubes.

The ‘Fouts and Fowler Gallery’ opened in Fitzrovia in 1989 and the corner plastic ice cream cone finial on the iron railings bears their initials NF & MF. The building is now the Coningsby Gallery and is at 30 Tottenham St, W1T 4RJ. If you go to see this, do also look for the paintbrush-bearing hands in the window frame.

For a long time, the railings were painted black and the ice cream was the colours you expect an ice cream and cone to be so it was easier to spot. It’s now painted grey to blend with the rest of the railings but is still a great ‘only those in the know’ kind of thing to point out.

3. Bronze Mitten

Another sculpture that’s missed by most is a small pink mitten on a railing outside the Foundling Museum in Bloomsbury. It looks like something lost by a child and popped on the railing so it doesn’t blow away and so the family may find it to go with its partner. But it’s actually a bronze sculpture by Tracey Emin.

Emin found the mitten on the street and decided to cast and paint it for this permanent addition to the railings outside the children’s charity Coram.

Originally, this mitten was one of the ‘Baby Things‘ series created for the first Folkestone triennial art show in 2008 highlighting the issue of teenage pregnancy. This cast was made for the ‘Mat Collishaw, Tracey Emin and Paula Rego: at the Foundling‘ exhibition in 2010 which included other items from her ‘Baby Things‘ series: a tiny sock, the mitten and a teddy cast in bronze.

To find the mitten, head to the Foundling Museum at 40 Brunswick Square, WC1N 1AZ, and look to the right of the museum entrance to see the Thomas Coram statue. Look at the railings behind and to the left of the statue and you’ll see this very small artwork by a famous artist.

4. Little Compton Street

You may know this one as I wrote a blog post about it. Cross Charing Cross Road, north of Cambridge Circus and near the junction with Old Compton Street, and stop on the traffic island. Through the grille, you should be able to see two signs for Litle Compton Street.

Many will tell you this is a buried London street but I’ve explained what it really is in the blog post which includes links to see what it’s like under there.

5. Mice on a Wall

The Two Mice Eating Cheese is on Philpot Lane, near the entrance to the Sky Garden.

Everyone (who knows) will tell you these rodents are on the wall to commemorate the death of a workman in the City of London. Some say two men were working on the construction of The Monument nearby in the 1670s and others will tell you it was two men who worked on the Victorian building where the sculpture can be seen. The story goes that these two men were friends and were on their lunch break, high above ground level. Lunch was bread and cheese and when one opened his lunchbox his food was gone. He got angry with his friend and accused him of stealing his lunch. The men fought and one or both of them fell to the ground and died.

But the excellent IanVisits has debunked this ‘legend’ as while it is what most will tell you happened, there is no written record that any of that is true. The earliest written record is in the Daily Mirror in 1974. An alternative idea for the mice sculpture is offered that the workmen who built the Victorian building shared their lunch with mice so wanted to include them. Yet IanVisits checked the write-up about the building’s opening in The Builder newspaper and the mice are not mentioned. So it would seem that this is one of those stories that we like to pass on to each other but may have little connection to truth.

The mice can be seen on Philpot Lane near the junction with Eastcheap. Look above the arches to the first-floor level and the mice are at the join with the slightly set back section of the building on the left. The sculpture is at the same height as the street sign.

6. Chewing Gum Street Art

Street art comes in many shapes and sizes. Ben Wilson has been painting tiny works of art on discarded chewing gum since 2004. His chewing gum art on the Millennium Bridge – the footbridge between St Paul’s Cathedral and Tate Modern – is probably his most well-known location. But you can also unexpectedly find his chewing gum street art across north and central London. (I’ve spotted pieces in Crouch End, Muswell Hill, Camden and Fitzrovia.)

To create the artwork, he first uses a blowtorch to smooth out the discarded gum and then adds coats of lacquer and acrylic enamel. He uses modellers’ brushes to paint the designs which are often requested by those who live or work nearby. It can take him many hours to complete one artwork but it can last for years.

Wilson has been threatened with the courts in the past but he has found a clever legal loophole as he is not painting public property or commercially owned real estate. And chewing gum has no food value, hardly biodegrades and is costly to remove. Wilson’s street art brings joy to many so do say hello and thank him if you spot him lying down painting on a bridge or street on your travels.

7. Giro the Dog Grave

I’ve heard this described as the only Nazi memorial in London. But Giro was German and not a Nazi (can dogs have a political persuasion?) The dog was owned by Dr Leopold von Hoesch who was the German Ambassador in London from 1932 to 1936.

Giro died in 1934 from accidental electrocution (contact with an exposed wire). He was so well-loved that he was buried near the then-German Embassy and we can still see a small tombstone. It has the German epitaph “Giro: Ein treuer Begleiter” which means “Giro: A true companion”.

From 1936 to 1939, the German Embassy in London was at 9 Carlton House Terrace. (The building is now occupied by the Royal Society.) Albert Speer, the Nazi architect, was involved in the building’s thorough renovation and the interior boasts a staircase made from Italian marble, which is said to have been donated by Mussolini.

The Germans had to leave when the war started and The Foreign Office used the building from 1939. They attempted to remove most of the swastikas but there is a border design of swastikas on the floor of one public room.

As you might expect, the tombstone is much smaller than normal. It is preserved in a wooden box with a clear front (although this is often quite dirty making it hard to view).

You’ll find it on Waterloo Place, London SW1Y 5AG. It is under the tree, at the top of the steps, close to the enormous statue of the Duke of York on a tall column. The tombstone is in a small space that was once the front garden of 9 Carlton House Terrace but is not directly in front of the building. It is on the other side of the garage ramp.

8. Admiralty Arch Nose

Another thank you to Peter Berthoud who introduced me to the Seven Noses of Soho. There was a legend that spread quickly that if you found them all you would have great wealth. I think that highlights how hard they were to find but it was all a bit of fun by an artist called Rick Buckley.

In 1997, Buckley fixed 35 noses to walls but many were spotted on landmarks and removed quite quickly. All were plaster of Paris reproductions of his nose. Seven remained for a long time and some can still be found.

The myths about the one on Admiralty Arch are good. Because of the height of the installation, it’s said that it was modelled on Napoleon’s nose and placed there so mounted cavalry could tweak it as they passed. Others say it’s the Duke of Wellington’s nose and could be rubbed by mounted cavalry for good luck. And I’ve even heard it said that this was a spare for Nelson atop his column in nearby Trafalgar Square.

When approaching Admiralty Arch from Trafalgar Square, the nose is on the right arch on the inner side.

Nothing to do with Buckley this time, there’s also a nose fixed to the wall in Meard Street in Soho (just off Dean Street, W1). I think this one has been here even longer.

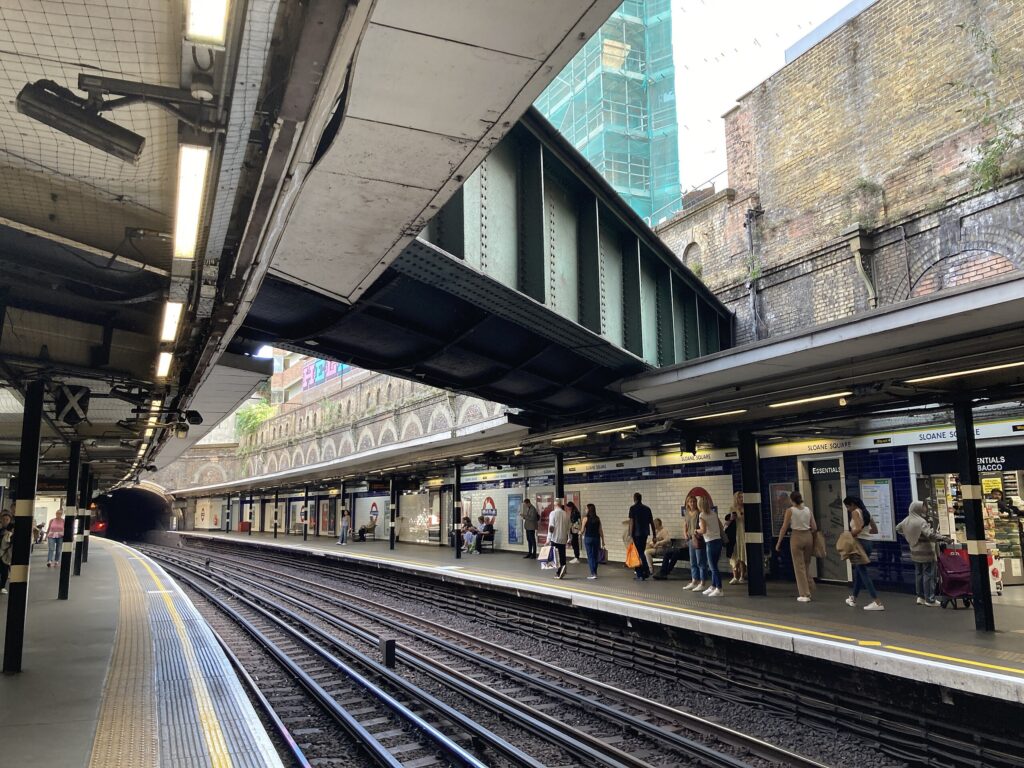

9. River Over A Tube Station

If you’re catching a Circle or District or line tube at Sloane Street station, this is a quirky thing to point out. Over the platforms, you can see a large iron pipe. What you can’t see is that this carries The River Westbourne – one of London’s lost rivers. The Westbourne flowed from Hampstead Heath, through Hyde Park and out into The Thames in Chelsea.

In the 19th century, when London’s population boomed, many of the city’s tributaries were forced into sub-surface pipes or sewers. As the tube network is also sub-surface, a different idea was needed for Sloane Square station which opened in 1868.

Clever behind-the-scenes Victorian engineering pumps culvert the water from the River Westbourne up into this conduit. It’s a storm drain and combined sewer so we can remain grateful it is covered.

Even though the station was bombed in 1940 during World War Two, the pipe wasn’t damaged and this is still the original.

10. The Millbank Prison Moat

Did you know, Tate Britain is on the site of a prison? Millbank Prison was here from 1816 to 1890. Due to bad planning/forward-thinking, the prison’s terrible ventilation system meant diseases spread easily and the labyrinthine design meant prison officers often got lost.

After Pentonville Prison opened in 1842, Millbank was downgraded to a holding depot for convicts being deported to Australia. Then from 1870, it served as a military prison for its last twenty years.

Why am I telling you all this? When you walk to Tate Britain from Pimlico tube station you can pass the remains of the prison moat. Exit the station onto Bessborough Street and walk to the junction with Vauxhall Bridge Road. Cross straight over and go down Causton Street. Turn right onto Ponsonby Place and then left onto John Islip Street. Stay on the lefthand side of the road and look behind the buildings on that corner. Behind Wilkie House, you can see the area that was the prison moat. It’s now a community garden and is often used for drying washing.

If you want to see more remnants of the Millbank Prison, Londown Under has this self-guided walking tour.

Bonus: Westminster Tiles

In St Stephen’s Hall inside the Houses of Parliament, there is something quirky about the lions on the encaustic floor tiles. The tiles along the edge of the room have lions with their eyes open and the lions down the centre of the Hall have their eyes closed. It’s said the reason for this is so ladies in large dresses could walk down the middle of the room without the lions looking up their skirts!